Corn stunt spiroplasma (CSS) resurging in the southern United States.

As temperatures rise and weather patterns shift, the challenges facing corn growers become more complex. Corteva senior scientist and global phytosanitary risk mitigation lead Scott Heuchelin says the southern U.S. is experiencing a resurgence of corn stunt spiroplasma. Heuchelin also leads the American Seed Trade Association (ASTA) phytosanitary committee.

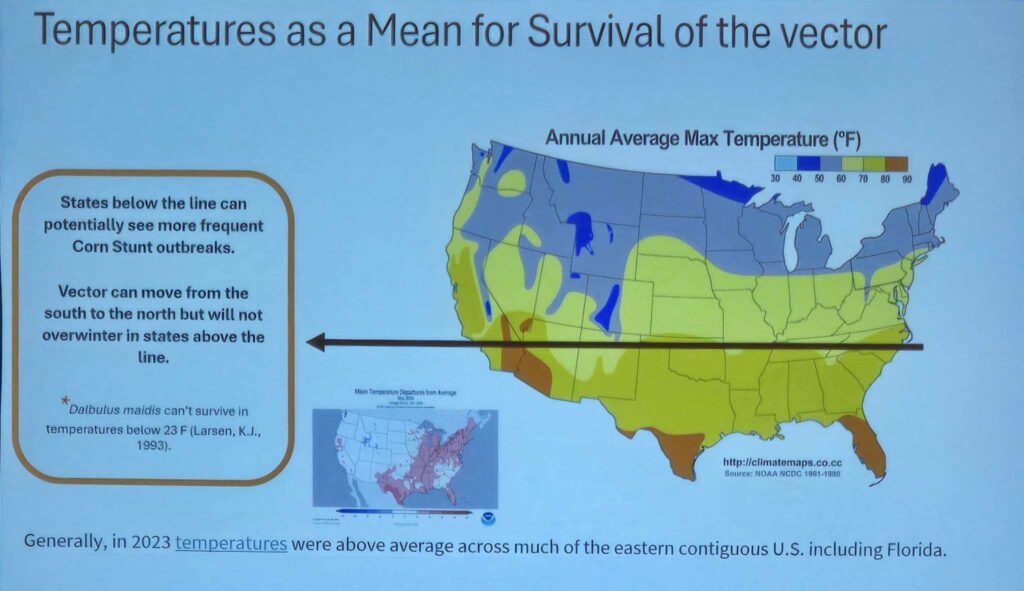

“Corn stunt has been around before; it’s nothing new. It’s common in Latin America and the southern U.S., but with warming trends, we’re seeing it move farther north,” Heuchelin said. “In 2024, above-normal temperatures allowed it to spread into areas where it typically doesn’t survive. This year, the very first detections were in Texas and then moving up through the Great Plains. But storm systems can move it very far – it even showed up in New York toward the end of the season this year.”

The discussion was part of the phytosanitary session at the ASTA Field Crop Seed Conference in Orlando, Florida.

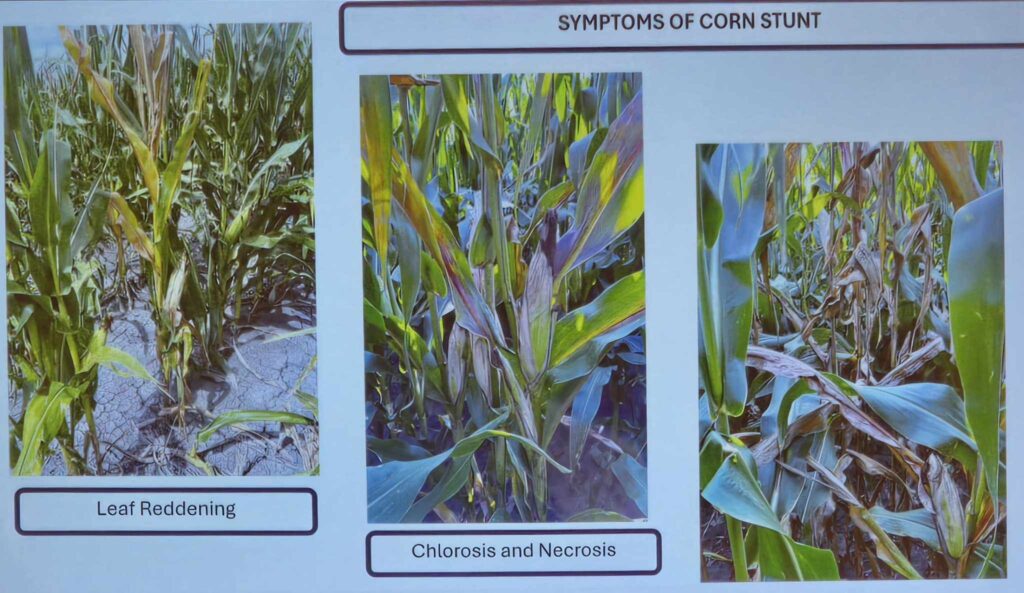

“Corn stunt is very much environment-dependent,” Heuchelin explained. “It’s caused by Spiroplasma kunkelii, which is introduced by the corn leafhopper. The symptoms you see —chlorosis, reddish discoloration and stunting — are a result of the pathogen disrupting nutrient movement in the phloem.”

Heuchelin said the disease often catches farmers off guard.

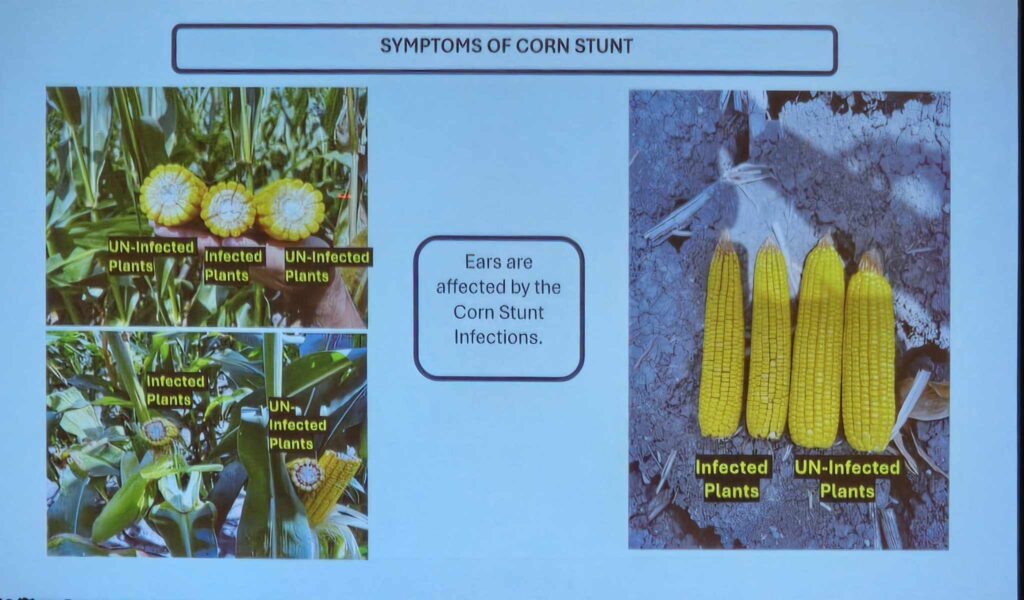

“What we’re seeing isn’t just leaf symptoms — it impacts yield,” he said. “Infected ears are smaller, poorly filled and lead to low test-weight grain,” he noted, sharing images of stunted ears. “This is all part of the plant shutting down prematurely.”

The culprit, the corn leafhopper, thrives in warmer temperatures.

Managing Corn Stunt

“Scouting is critical,” Heuchelin emphasized. “Use sticky traps to monitor leafhopper populations, and when you see symptoms, get samples sent for diagnosis.”

Early detection allows growers to take action before the disease becomes widespread.

Crop rotation and green bridge management are also vital.

“The vector can survive on wheat and sorghum, so managing volunteer corn and alternative hosts helps break the cycle,” he said. “We also need to be cautious with planting cycles. Overlapping plantings or fields with corn nearby can create a continuous reservoir for the disease.”

He gave advice on insect control

“If scouting reveals significant vector pressure, insecticides are an important tool. Combined with hybrid selection, we can mitigate yield loss,” he said.

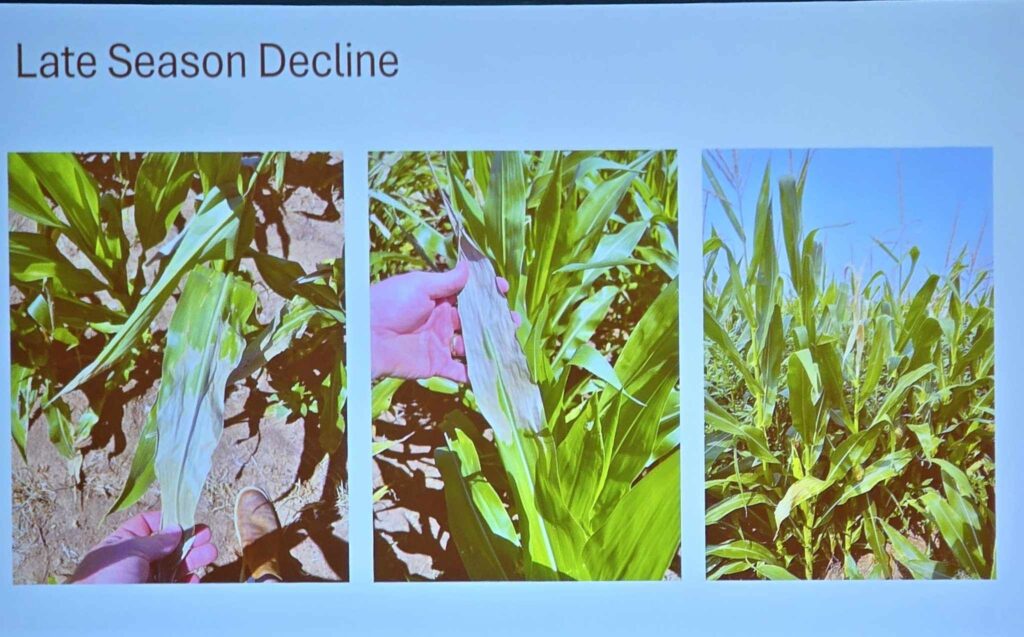

The Mystery of Late Season Decline

Heuchlin said Late Season Decline presents a different kind of challenge.

“We’re seeing symptoms like water-soaked lesions, streaks and necrotic patches, especially under stressful conditions like high heat and drought,” Heuchelin shared. “But we’re still figuring out what’s really going on.”

At the heart of the uncertainty is the role of bacterial pathogens like Pantoea ananatis. “This bacterium is everywhere — it exists inside plants, outside plants and even on crops like onions,” Heuchelin said. “But we don’t fully understand what makes it pathogenic in some cases and not in others.”

The implications are significant for seed exports.

“If we don’t develop specific tests to differentiate pathogenic from non-pathogenic strains, false positives could halt our seed exports,” he warned.

Despite the challenges, Heuchelin offered a measured perspective.

“I wouldn’t panic about Late Season Decline, but it’s important to be informed,” he said. “There’s work to do in understanding whether this is truly a disease or just bacteria taking advantage of stressed tissue.”

For growers, Heuchelin urged vigilance.

“Scout your fields. Manage stress. And stay informed as research continues,” he said. “These challenges are manageable, but they require vigilance and action.”

By focusing on early detection, vector control and careful management, Heuchelin’s insights offered tools to navigate these emerging threats. As he put it, “It’s all about breaking the cycle and staying ahead of the game.”

The post Emerging Corn Diseases appeared first on Seed World.